I've had to create several rubrics for managers to use to measure a set of staff skills and behaviors.

Here's the set up. A library I am working with has defined several outcomes they want to achieve for staff - staff will do such and such behavior related to excellent customer service or staff will know how to do such and such a task related to technology skills. We've decided to measure these outcomes using rubrics that managers will fill out for each staff member (think how the SAT grades writing on the 1 to 6 scale). Because the library is trying to develop new skills and behaviors for staff, the purpose of the rubrics is not to be a performance review for staff to punish or reward them, but instead to identify areas where further training or focus is needed.

Everyone at the library is busy and has too much on their plate as it is. So we wanted to triangulate between a measurement that is quick, painless, and accurate. Rubrics seemed like an interesting way to go.

I did some investigating and started following the standard format that rubrics take. (btw, I found this website to be a great resource for baseline info on rubrics: http://www.carla.umn.edu/assessment/vac/evaluation/p_7.html.) Essentially, you end up with a scoring grid with 2 axis. On the vertical access you have the different categories that behavior is measured against. If the overall outcome has to do with customer service, then the categories might be "attitude, accessibility, accuracy" (brief nod to the alliteration). On the horizontal access, you have the scoring levels. There are often 4 or 6 levels (even-numbers to avoid the tendency to put everyone in the center), for example "exemplary, "superior, very good, fair, needs work".

Looks something like this:

The final step is to fill in each grid in your table with a description of what the outcome would look like, for each category and each level. The problem is, this leaves you with a pretty dense table of text. If you have three categories and four levels, that's 12 paragraphs of text that someone has to read through and take a measurement on.

Now looks something like this:

Not the quick and painless solution we were looking for.

After wrestling with this for a while, here's the solution I came up with. Instead of describing each level for each category, I preface the table with a general description of each level for performance. Then the table describes the ideal performance for each category.

So managers start off reading something like this:

4 – Exemplary. Matches the Ideal perfectly. You would describe every characteristic with words like “always, all, no errors, comprehensive”.

3 – Excellent. A pretty close match to the Ideal, but you can think of a few exceptions. You would describe some characteristics with words like “usually, almost all, very few errors, broad”, even if other characteristics are at a 4 level.

2 – Acceptable. Matches the Ideal in many respects, but there are definitely areas for improvement. You would describe some characteristics with words like “often, many, few errors, somewhat limited”, even if other characteristics are at a 4 or 3 level.

1 – Not there yet. Some matches with the Ideal, but many areas where improvement is needed. You would describe some characteristics with words like “sometimes, some, some errors, limited”.

Then they look at the table of idealized characteristics, and jot down their ranking, which looks something like this:

This nice thing about this is that once they read through that initial description of performance levels, they can fill out any number of rubrics for various outcomes and know exactly what the scoring criteria are, without having to read something new each time. Triangulation of quick, painless, and accurate. Check!

Note: drawings done using http://dabbleboard.com

Integrated Evaluation

Monday, April 23, 2012

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

How to analyze interview data

Every time I conduct structured or semi-structured interviews as part of an evaluation, I feel a bit overwhelmed when I open the folder on my computer with the interview transcripts. How do I take all of this text and turn it into something meaningful?

I'm still working out different techniques, but I've been surprised how much I end up getting out of going through the following simple routine.

Step 1. I open a new word document and write out main questions that the interview was meant to answer. If I was looking for anything specific (e.g. a story about a frustrating visitor experience or an idea for how the library could be more user-friendly for seniors) then I'll also write that down.

These become my main section headings for analyzing the data.

Step 2. I read through each interview and copy/paste sections of the interview under the appropriate section heading. I try to do this thoughtfully but not agonizingly. I usually set a timer to keep myself from getting bogged down in hyper-interpretation. I often set the original interview text in italics once it's been copy/pasted once. That way I can skip sections that I don't know what to do with and come back to them later.

Step 3. I read through my categorized document and start shifting quotes around, as needed. Sometimes I'll put a quote in 2 different places, but not often. I've found that if I do that too much, I end up with way too many categories and subcategories. Keep it simple.

Step 4. I take some time away from the analysis. A day or two, if possible.

Step 5. I go through step 3 again.

Step 6. I look over my data and ask myself, "so what?" This is where the fun interpretation stage comes in. Once I get to this point, I've found that I'm familiar enough with the data to really be able to question my assumptions and be intellectually honest about whether my assessment is founded in fact or in preconception.

I'm still working out different techniques, but I've been surprised how much I end up getting out of going through the following simple routine.

Step 1. I open a new word document and write out main questions that the interview was meant to answer. If I was looking for anything specific (e.g. a story about a frustrating visitor experience or an idea for how the library could be more user-friendly for seniors) then I'll also write that down.

These become my main section headings for analyzing the data.

Step 2. I read through each interview and copy/paste sections of the interview under the appropriate section heading. I try to do this thoughtfully but not agonizingly. I usually set a timer to keep myself from getting bogged down in hyper-interpretation. I often set the original interview text in italics once it's been copy/pasted once. That way I can skip sections that I don't know what to do with and come back to them later.

Step 3. I read through my categorized document and start shifting quotes around, as needed. Sometimes I'll put a quote in 2 different places, but not often. I've found that if I do that too much, I end up with way too many categories and subcategories. Keep it simple.

Step 4. I take some time away from the analysis. A day or two, if possible.

Step 5. I go through step 3 again.

Step 6. I look over my data and ask myself, "so what?" This is where the fun interpretation stage comes in. Once I get to this point, I've found that I'm familiar enough with the data to really be able to question my assumptions and be intellectually honest about whether my assessment is founded in fact or in preconception.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Simple evaluation tool - the card sort

One of my favorite evaluation tools in the Card Sort. To understand visitors' perspective on something, hand them a stack of cards, each with a 1-2 word description of the topic you have in mind. Ask visitors to pull out the words that best and least describe the topic (limit them to 3-4; many people will want to pull out 8 or 9 cards). Then follow up and ask them why they chose the cards they did.

When you analyze the data, it's interested to add them the numbers for what cards were chosen the most, and which cards were ignored the most. Add to that some really great qualitative information about why people made their selections. Often, you find that people have different interpretations of the words than you, as the researcher, had.

Here's an example. Let's say you want to know how people perceive the library's current collection of fiction. Put together a list of 10-15 words that could possibly describe the collection - and don't be afraid to include some negative words (good selection, new materials, lots of options, worn out, not relevant to me, etc). The words you choose are important. Keep them simple, so people can process them quickly. But be specific and even a bit daring - that will bring out interesting comments and discussion. Above all, make sure they are relevant to what you want to know about. Test your words with a few people from the organization. Then try the list out on a few patrons before going live with the study.

As a rule of thumb, when you go live, ask as many people to do the card sort as it takes until you feel like answers are getting redundant. If you must have a number, I would recommend 30 people as a minimum.

To analyze results, tally up the total of "best" and "worst" hits each word got. Then compare what people said as their reasons why they chose those words. What patterns or themes do you see? One note: the more accurately you transcribe people's responses to why they chose words, the better your qualitative analysis will be. Resist the temptation to summarize people's statements when collecting the data. Try to write down what they say as close to word-for-word as possible. It's tough, but worth it. You don't want to add your layer of interpretation until all the data is collected.

When you analyze the data, it's interested to add them the numbers for what cards were chosen the most, and which cards were ignored the most. Add to that some really great qualitative information about why people made their selections. Often, you find that people have different interpretations of the words than you, as the researcher, had.

Here's an example. Let's say you want to know how people perceive the library's current collection of fiction. Put together a list of 10-15 words that could possibly describe the collection - and don't be afraid to include some negative words (good selection, new materials, lots of options, worn out, not relevant to me, etc). The words you choose are important. Keep them simple, so people can process them quickly. But be specific and even a bit daring - that will bring out interesting comments and discussion. Above all, make sure they are relevant to what you want to know about. Test your words with a few people from the organization. Then try the list out on a few patrons before going live with the study.

As a rule of thumb, when you go live, ask as many people to do the card sort as it takes until you feel like answers are getting redundant. If you must have a number, I would recommend 30 people as a minimum.

To analyze results, tally up the total of "best" and "worst" hits each word got. Then compare what people said as their reasons why they chose those words. What patterns or themes do you see? One note: the more accurately you transcribe people's responses to why they chose words, the better your qualitative analysis will be. Resist the temptation to summarize people's statements when collecting the data. Try to write down what they say as close to word-for-word as possible. It's tough, but worth it. You don't want to add your layer of interpretation until all the data is collected.

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Data collection is fun - and not just for you

Here is a somewhat dated evaluation done at the San Jose Children's Discovery Museum, but I thought their qualitative methods were interested.

http://www.hfrp.org/out-of-school-time/ost-database-bibliography/database/discovery-youth

In the first evaluation, they did focus groups with youth were they divided the youth into teams of 2-3 and had them fill the in the answers to 4 open-ended questions. Then they brought all the teams together (about 4 total) and had them discuss.

In the second evaluation, they did a group activity with program participants. Participants broke out into groups of 4-5. Then they circulated around the room to large pieces of paper with a different question written on each. Each group wrote answers on the large sheet of paper for each question, so they were able to react to a previous group's comments.

These techniques hit on 2 principles that I think are key to focus groups and interviews. First, make it fun. Vary the questions, get people up and moving, use the 5 senses, present extremes with humor.

Second, give them something to react to. I find I get much more detailed and colorful responses from people if I present something to them first and get their feedback on it. A list, a board full of written-on sticky notes, a photo, a written description. In both of the examples above, participants were responding to what other participants said. A key to that, I believe, is to have people commit to an opinion on paper first. If you jump into reactions right away, then less vocal opinions get lost.

http://www.hfrp.org/out-of-school-time/ost-database-bibliography/database/discovery-youth

In the first evaluation, they did focus groups with youth were they divided the youth into teams of 2-3 and had them fill the in the answers to 4 open-ended questions. Then they brought all the teams together (about 4 total) and had them discuss.

In the second evaluation, they did a group activity with program participants. Participants broke out into groups of 4-5. Then they circulated around the room to large pieces of paper with a different question written on each. Each group wrote answers on the large sheet of paper for each question, so they were able to react to a previous group's comments.

These techniques hit on 2 principles that I think are key to focus groups and interviews. First, make it fun. Vary the questions, get people up and moving, use the 5 senses, present extremes with humor.

Second, give them something to react to. I find I get much more detailed and colorful responses from people if I present something to them first and get their feedback on it. A list, a board full of written-on sticky notes, a photo, a written description. In both of the examples above, participants were responding to what other participants said. A key to that, I believe, is to have people commit to an opinion on paper first. If you jump into reactions right away, then less vocal opinions get lost.

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

Expanding the Customer Experience - And A Simple Way to Get Started

Most cultural organizations are focusing in on customer experience as a key to long-term success. Visitors who have a good experience, come again, and again. They bring other people, they talk about you, they may even turn from visitors to donors.

But when we think about customer experience, we often do so with blinders on. Let's say you're a history museum. What's the customer experience? A family walks in to the museum, pays admission, visits galleries, maybe interacts with some guides or docents, checks out the gift shop on the way out, and leaves.

With that perspective, how do we improve customer experience? We make sure visitors can easily find the admission desks, we train employees to be friendly and welcoming, we focus on great content in the galleries, we have fun and interesting items in the gift shop.

There are 2 problems with this kind of brainstorming. #1: It is focused on the customer experience from the perspective of the institution only. #2 (and following from #1): It leaves out the Why.

#1. Institution-focused perspective

Think about the experience of going out for ice cream. What does it look like? You pull up to the shop with your family, head inside, look at the many choices, make your selections, pay, eat and enjoy the ice cream, and leave.

Okay, take the first one. You pull up to the shop. Hang on a sec. What happened before you pulled up? Well, you had to decide which ice cream shop to go to. What about before that? You had to decide to take the whole family out to ice cream. Maybe it was a choice between ice cream or a different treat. Maybe this is a routine thing you do on Wednesday nights. Maybe you're celebrating something or someone special.

Now the other side. What happens after you leave? You worry about sticky hands on the car upholstery. You laugh and joke on the way home. Your kids thank you for the outing. You post photos on your blog of the family trip.

Lesson? There's a whole lot more to getting ice cream than what happens at the shop.

As I talked about earlier, you can look at customer experience as having 5 parts: Entice (when people are thinking they want what you have), Enter (investigating you, calling, looking up online), Engage (decided to come or to purchase), Exit (conclude visit or purchase), Extend (think about it, talk about it, want it, later on). Institutions usually focus on the third, Engage. But your customers' experience has already started and will continue after.

#2. Getting at Why.

It's important to recognize this wider range of the customer experience because it will help you think about the why behind your customer engagement. When you think about how people got to you, you start to think about why they came. What situation were they in? What need were they trying to fill? Is it different for different people?

Asking these questions will help you think about what to change once visitors get to the Engage step. It will also help you think about how you can reach your visitors before they get to that step, and what potential their is for extending beyond the engage/exit.

Want to incorporate this thinking in your organization?

Here's a simple strategy to use to get people thinking in these broader terms of the customer experience. On small cards, write down brief sentences describing a typical experience (getting ice cream, buying golf clubs). Include sentences from each of the 5 aspects of the customer experience. Have some of the cards be positive things (found a parking space!) and some be negative things (couldn't figure out how to call customer service). Shuffle the cards up, and have people sort through the cards to put them in order of what they would do in this experience. Once they do this, draw the analogy to your organization. How would you re-write some of the cards for our organization? Push the card up higher if we're doing this well. Push it down lower if we're doing it poorly. What do we need to work on?

But when we think about customer experience, we often do so with blinders on. Let's say you're a history museum. What's the customer experience? A family walks in to the museum, pays admission, visits galleries, maybe interacts with some guides or docents, checks out the gift shop on the way out, and leaves.

With that perspective, how do we improve customer experience? We make sure visitors can easily find the admission desks, we train employees to be friendly and welcoming, we focus on great content in the galleries, we have fun and interesting items in the gift shop.

There are 2 problems with this kind of brainstorming. #1: It is focused on the customer experience from the perspective of the institution only. #2 (and following from #1): It leaves out the Why.

#1. Institution-focused perspective

Think about the experience of going out for ice cream. What does it look like? You pull up to the shop with your family, head inside, look at the many choices, make your selections, pay, eat and enjoy the ice cream, and leave.

Okay, take the first one. You pull up to the shop. Hang on a sec. What happened before you pulled up? Well, you had to decide which ice cream shop to go to. What about before that? You had to decide to take the whole family out to ice cream. Maybe it was a choice between ice cream or a different treat. Maybe this is a routine thing you do on Wednesday nights. Maybe you're celebrating something or someone special.

Now the other side. What happens after you leave? You worry about sticky hands on the car upholstery. You laugh and joke on the way home. Your kids thank you for the outing. You post photos on your blog of the family trip.

Lesson? There's a whole lot more to getting ice cream than what happens at the shop.

As I talked about earlier, you can look at customer experience as having 5 parts: Entice (when people are thinking they want what you have), Enter (investigating you, calling, looking up online), Engage (decided to come or to purchase), Exit (conclude visit or purchase), Extend (think about it, talk about it, want it, later on). Institutions usually focus on the third, Engage. But your customers' experience has already started and will continue after.

#2. Getting at Why.

It's important to recognize this wider range of the customer experience because it will help you think about the why behind your customer engagement. When you think about how people got to you, you start to think about why they came. What situation were they in? What need were they trying to fill? Is it different for different people?

Asking these questions will help you think about what to change once visitors get to the Engage step. It will also help you think about how you can reach your visitors before they get to that step, and what potential their is for extending beyond the engage/exit.

Want to incorporate this thinking in your organization?

Here's a simple strategy to use to get people thinking in these broader terms of the customer experience. On small cards, write down brief sentences describing a typical experience (getting ice cream, buying golf clubs). Include sentences from each of the 5 aspects of the customer experience. Have some of the cards be positive things (found a parking space!) and some be negative things (couldn't figure out how to call customer service). Shuffle the cards up, and have people sort through the cards to put them in order of what they would do in this experience. Once they do this, draw the analogy to your organization. How would you re-write some of the cards for our organization? Push the card up higher if we're doing this well. Push it down lower if we're doing it poorly. What do we need to work on?

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Experience Economy Frameworks (cont)

Continuing to document the frameworks I learned while talking to Kathy Macdonald.

The Values of An Experience

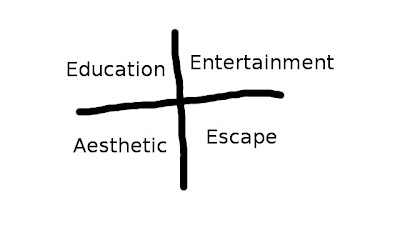

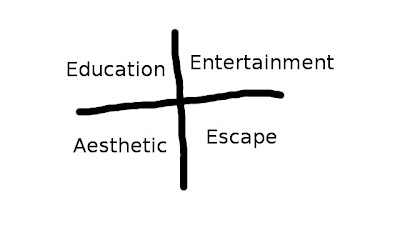

People value 4 basic things in an experience: education (what did I learn? how am I different?), entertainment (did it make me laugh? did it feel fun and interesting?), aesthetic (was it comfortable? was it beautiful?), and escape (did I lose track of time? did I feel like I was somewhere else for a little while?).

Problem vs Pain

When an organization brings on a consultant, it's usually because they've identified some problem they want help dealing with. For example, a museum may say that they want to increase visitors coming through the doors on weekends. That's their problem. But it's worth digging in to what their pain is. Maybe their pain is that their revenue is steadily decreasing. Or they put a lot of resources into weekend programming and aren't seeing a return. The pain gets at why the problem is a problem.

Ways to Change the Experience

When an organization is looking at changing the customer experience, they have 3 ways to go about it. First, the physical environment: what people see when they come and how it makes them feel. Think colors, textures, furniture, light. Second, the process: how people find their way, what they can (and can't do). Think signage, walkways, admissions or reference desks. Finally, human: the people they interact with and how they interact with them. Think front desk staff, docents, guides.

The Change Timeline

When organizations recognize they have a new vision, strategy, or direction to pursue, they often want to get there right away. Practically speaking, change takes time. This framework says 3 years. The yellow scribble at the end of 3 years is the organization's vision of where they want to be. It's a scribble because, while it's got some definition, it's still going to be vague - it will shift and grow and become defined in this 3-year process.

At the beginning of the timeline is the Ending. Organizations often start the vision/strategy process by identifying that there are things they want to stop. Things that aren't working right. Next, they move into Neutral. This is where they are trying new things out (hence the squiggly lines - guess and check, trial and error). They expect some failure, they expect some success. Finally they get to the Beginning. They've identified a few things that work. They move forward, full speed ahead.

The check marks at the bottom are check points for the organization. It's easy to get discouraged and to feel like things are never going to take shape. By making a list of milestones in advance, then organizations can point those out as signs that they're on the right track.

The Values of An Experience

People value 4 basic things in an experience: education (what did I learn? how am I different?), entertainment (did it make me laugh? did it feel fun and interesting?), aesthetic (was it comfortable? was it beautiful?), and escape (did I lose track of time? did I feel like I was somewhere else for a little while?).

Problem vs Pain

When an organization brings on a consultant, it's usually because they've identified some problem they want help dealing with. For example, a museum may say that they want to increase visitors coming through the doors on weekends. That's their problem. But it's worth digging in to what their pain is. Maybe their pain is that their revenue is steadily decreasing. Or they put a lot of resources into weekend programming and aren't seeing a return. The pain gets at why the problem is a problem.

Ways to Change the Experience

When an organization is looking at changing the customer experience, they have 3 ways to go about it. First, the physical environment: what people see when they come and how it makes them feel. Think colors, textures, furniture, light. Second, the process: how people find their way, what they can (and can't do). Think signage, walkways, admissions or reference desks. Finally, human: the people they interact with and how they interact with them. Think front desk staff, docents, guides.

The Change Timeline

When organizations recognize they have a new vision, strategy, or direction to pursue, they often want to get there right away. Practically speaking, change takes time. This framework says 3 years. The yellow scribble at the end of 3 years is the organization's vision of where they want to be. It's a scribble because, while it's got some definition, it's still going to be vague - it will shift and grow and become defined in this 3-year process.

At the beginning of the timeline is the Ending. Organizations often start the vision/strategy process by identifying that there are things they want to stop. Things that aren't working right. Next, they move into Neutral. This is where they are trying new things out (hence the squiggly lines - guess and check, trial and error). They expect some failure, they expect some success. Finally they get to the Beginning. They've identified a few things that work. They move forward, full speed ahead.

The check marks at the bottom are check points for the organization. It's easy to get discouraged and to feel like things are never going to take shape. By making a list of milestones in advance, then organizations can point those out as signs that they're on the right track.

Labels:

customer experience,

experience economy,

frameworks

Friday, July 1, 2011

Frameworks for an Experience Economy

I had a fascinating and inspiring discussion yesterday with Kathy Macdonald, and I wanted to capture a few of the takeaways from our conversation here.

Kathy works with businesses to help them be competitive in the Experience Economy. Her work comes from Joseph Pine and James Gilmore's work in that area, best known by their book The Experience Economy (an updated version to be released shortly). She is also a master at putting ideas into frameworks that businesses can use for thinking about problems and coming up with solutions - which is something that I absolutely love and strive to do.

Through the course of our conversation, Kathy shared with me a few interesting frameworks.

First, the 5 phases of a customer: Entice (or Anticipate), Enter, Engage, Exit, Extend. Most businesses think about their customer relations starting at the Engage phase - a customer walks in the door to buy something. However, for the customer the experience starts way before. Take the analogy of buying a new pair of shoes. The customer experience starts when she realizes her old running shoes are wearing thin or her dress shoes are looking out of date - the customer anticipates the need for shoes (or, from the business side, they entice the customer to consider needing shoes). The customer Enters when she picks up a phone to call a shoe store, or finds them on an online search. She Engages when she drives to the store, walks in the door, looks for and finds shoes. She Exits when she buys the shoes, walks out, drives home, and starts wearing the shoes. Extend comes as she realizes the shoes hold up well (or don't), fit well (or don't), or when the store contacts her with a follow up or to give her a coupon or ad.

Thinking about the whole arc of the customer experience really changes the way a business sees their role and their contact points with a customer. It also gives them a sense of what background (or baggage) customers may bring with them once they get to the Engage piece, and what potential there is to Extend.

More frameworks to come later...

Kathy works with businesses to help them be competitive in the Experience Economy. Her work comes from Joseph Pine and James Gilmore's work in that area, best known by their book The Experience Economy (an updated version to be released shortly). She is also a master at putting ideas into frameworks that businesses can use for thinking about problems and coming up with solutions - which is something that I absolutely love and strive to do.

Through the course of our conversation, Kathy shared with me a few interesting frameworks.

First, the 5 phases of a customer: Entice (or Anticipate), Enter, Engage, Exit, Extend. Most businesses think about their customer relations starting at the Engage phase - a customer walks in the door to buy something. However, for the customer the experience starts way before. Take the analogy of buying a new pair of shoes. The customer experience starts when she realizes her old running shoes are wearing thin or her dress shoes are looking out of date - the customer anticipates the need for shoes (or, from the business side, they entice the customer to consider needing shoes). The customer Enters when she picks up a phone to call a shoe store, or finds them on an online search. She Engages when she drives to the store, walks in the door, looks for and finds shoes. She Exits when she buys the shoes, walks out, drives home, and starts wearing the shoes. Extend comes as she realizes the shoes hold up well (or don't), fit well (or don't), or when the store contacts her with a follow up or to give her a coupon or ad.

Thinking about the whole arc of the customer experience really changes the way a business sees their role and their contact points with a customer. It also gives them a sense of what background (or baggage) customers may bring with them once they get to the Engage piece, and what potential there is to Extend.

More frameworks to come later...

Labels:

customer experience,

experience economy,

frameworks

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)